- Mailing Lists

- in

- 100X Scaling: How Figma Scaled its Databases

Archives

- By thread 5228

-

By date

- June 2021 10

- July 2021 6

- August 2021 20

- September 2021 21

- October 2021 48

- November 2021 40

- December 2021 23

- January 2022 46

- February 2022 80

- March 2022 109

- April 2022 100

- May 2022 97

- June 2022 105

- July 2022 82

- August 2022 95

- September 2022 103

- October 2022 117

- November 2022 115

- December 2022 102

- January 2023 88

- February 2023 90

- March 2023 116

- April 2023 97

- May 2023 159

- June 2023 145

- July 2023 120

- August 2023 90

- September 2023 102

- October 2023 106

- November 2023 100

- December 2023 74

- January 2024 75

- February 2024 75

- March 2024 78

- April 2024 74

- May 2024 108

- June 2024 98

- July 2024 116

- August 2024 134

- September 2024 130

- October 2024 141

- November 2024 171

- December 2024 115

- January 2025 216

- February 2025 140

- March 2025 220

- April 2025 233

- May 2025 239

- June 2025 303

- July 2025 40

100X Scaling: How Figma Scaled its Databases

100X Scaling: How Figma Scaled its Databases

😘 Kiss bugs goodbye with fully automated end-to-end test coverage (Sponsored)Bugs sneak out when less than 80% of user flows are tested before shipping. But getting that kind of coverage — and staying there — is hard and pricey for any sized team. QA Wolf takes testing off your plate: → Get to 80% test coverage in just 4 months. → Stay bug-free with 24-hour maintenance and on-demand test creation. → Get unlimited parallel test runs → Zero Flakes guaranteed QA Wolf has generated amazing results for companies like Salesloft, AutoTrader, Mailchimp, and Bubble. 🌟 Rated 4.5/5 on G2 Learn more about their 90-day pilot Figma, a collaborative design platform, has been on a wild growth ride for the last few years. Its user base has grown by almost 200% since 2018, attracting around 3 million monthly users. As more and more users have hopped on board, the infrastructure team found themselves in a spot. They needed a quick way to scale their databases to keep up with the increasing demand. The database stack is like the backbone of Figma. It stores and manages all the important metadata, like permissions, file info, and comments. And it ended up growing a whopping 100x since 2020! That's a good problem to have, but it also meant the team had to get creative. In this article, we'll dive into Figma's database scaling journey. We'll explore the challenges they faced, the decisions they made, and the innovative solutions they came up with. By the end, you'll better understand what it takes to scale databases for a rapidly growing company like Figma. The Initial State of Figma’s Database StackIn 2020, Figma still used a single, large Amazon RDS database to persist most of the metadata. While it handled things quite well, one machine had its limits. During peak traffic, the CPU utilization was above 65% resulting in unpredictable database latencies. While complete saturation was far away, the infrastructure team at Figma wanted to proactively identify and fix any scalability issues. They started with a few tactical fixes such as:

These fixes gave them an additional year of runway but there were still limitations:

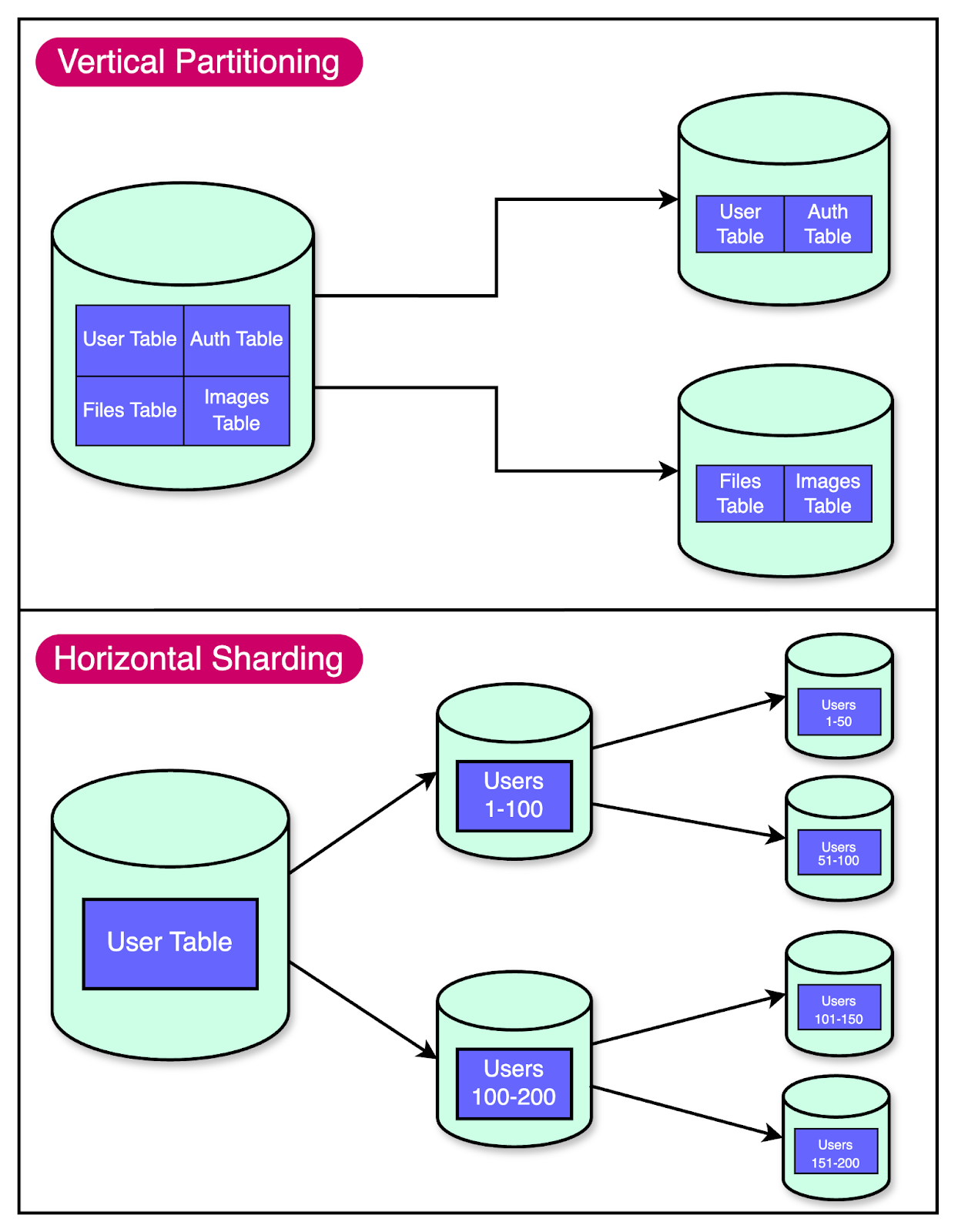

It was clear that they needed a longer-term solution. The First Step: Vertical PartitioningWhen Figma's infrastructure team realized they needed to scale their databases, they couldn't just shut everything down and start from scratch. They needed a solution to keep Figma running smoothly while they worked on the problem. That's where vertical partitioning came in. Think of vertical partitioning as reorganizing your wardrobe. Instead of having one big pile of mess, you split things into separate sections. In database terms, it means moving certain tables to separate databases. For Figma, vertical partitioning was a lifesaver. It allowed them to move high-traffic, related tables like those for “Figma Files” and “Organizations” into their separate databases. This provided some much-needed breathing room. To identify the tables for partitioning, Figma considered two factors:

For measuring impact, they looked at average active sessions (AAS) for queries. This stat describes the average number of active threads dedicated to a given query at a certain point in time. Measuring isolation was a little more tricky. They used runtime validators that hooked into ActiveRecord, their Ruby ORM. The validators sent production query and transaction information to Snowflake for analysis, helping them identify tables that were ideal for partitioning based on query patterns and table relationships. Once the tables were identified, Figma needed to migrate them between databases without downtime. They set the following goals for their migration solution:

Since they couldn’t find a pre-built solution that could meet these requirements, Figma built an in-house solution. At a high level, it worked as follows:

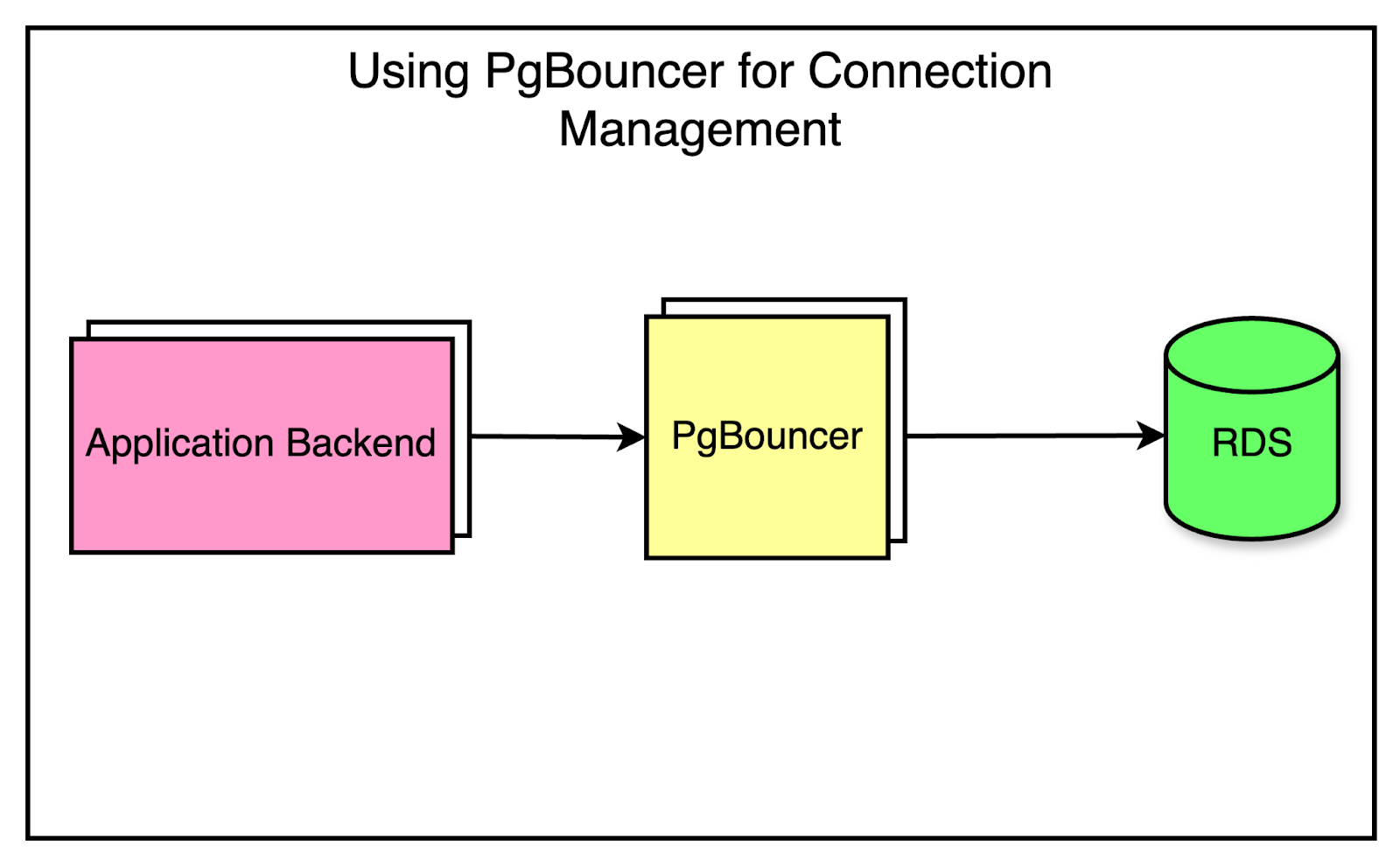

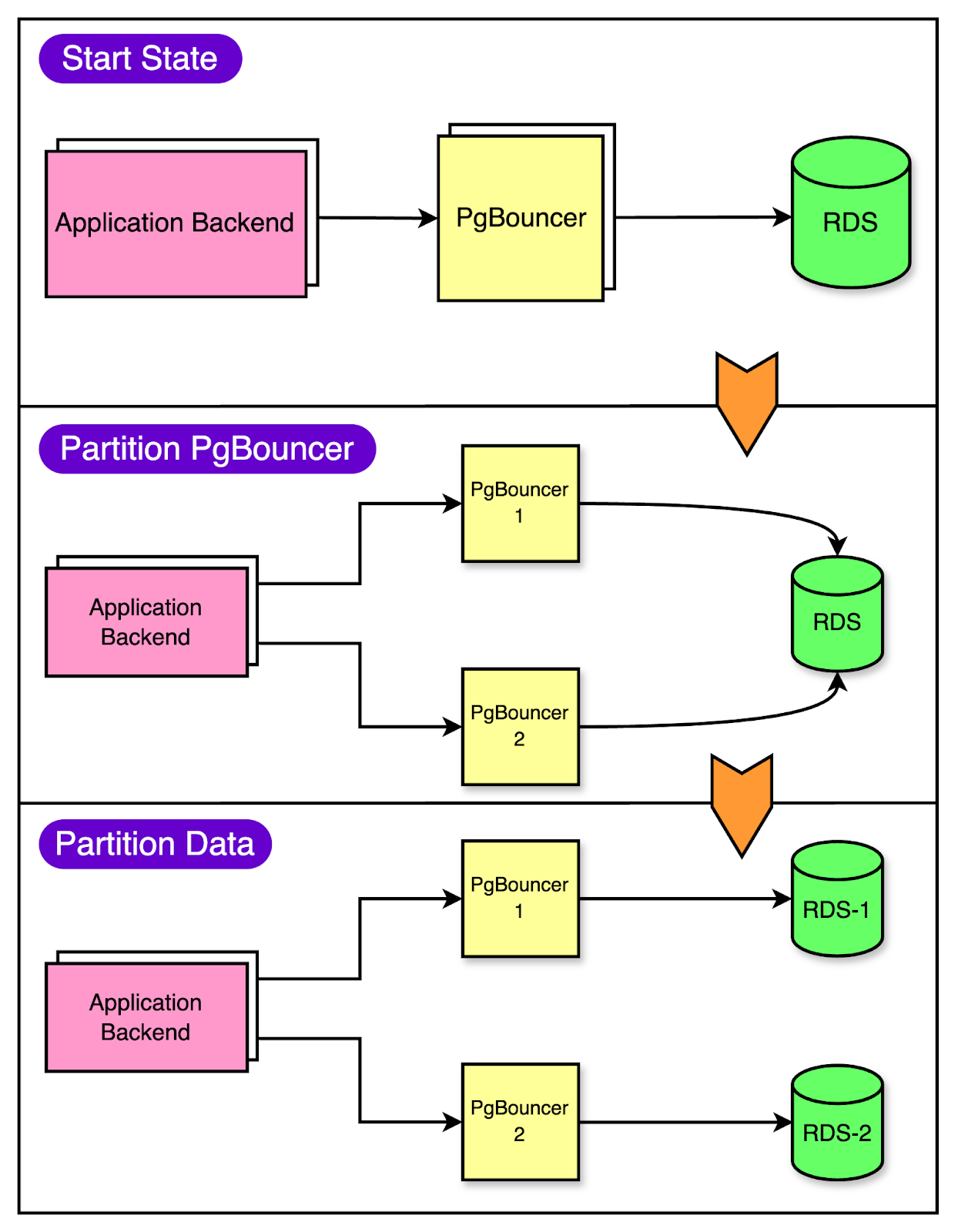

To make the migration to partitioned databases smoother, they created separate PgBouncer services to split the traffic virtually. Security groups were implemented to ensure that only PgBouncers could directly access the database. Partitioning the PgBouncer layer first gave some cushion to the clients to route the queries incorrectly since all PgBouncer instances initially had the same target database. During this time, the team could also detect the routing mismatches and make the necessary corrections. The below diagram shows this process of migration. Latest articlesIf you’re not a paid subscriber, here’s what you missed. To receive all the full articles and support ByteByteGo, consider subscribing: Implementing ReplicationData replication is a great way to scale the read operations for your database. When it came to replicating data for vertical partitioning, Figma had two options in Postgres: streaming replication or logical replication. They chose logical replication for 3 main reasons:

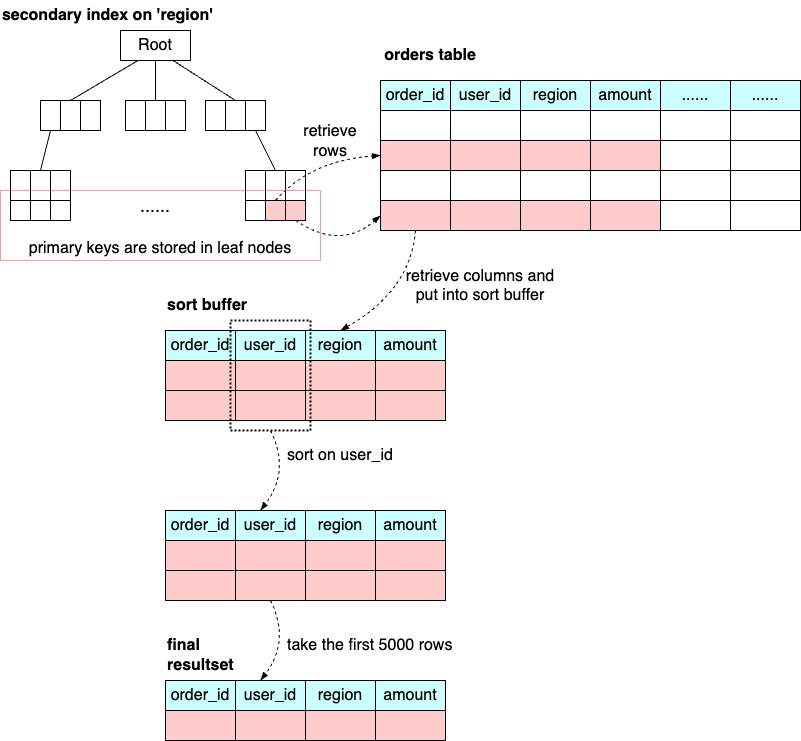

However, logical replication was slow. The initial data copy could take days or even weeks to complete. Figma desperately wanted to avoid this lengthy process, not only to minimize the window for replication failure but also to reduce the cost of restarting if something went wrong. But what made the process so slow? The culprit was how Postgres maintains indexes in the destination database. While the replication process copies rows in bulk, it also updates the indexes one row at a time. By removing indexes in the destination database and rebuilding them after the data copy, Figma reduced the copy time to a matter of hours. Need for Horizontal ScalingAs Figma's user base and feature set grew, so did the demands on their databases. Despite their best efforts, vertical partitioning had limitations, especially for Figma’s largest tables. Some tables contained several terabytes of data and billions of rows, making them too large for a single database. A couple of problems were especially prominent:

For a better perspective, imagine a library with a rapidly growing collection of books. Initially, the library might cope by adding more shelves (vertical partitioning). But eventually, the building itself will run out of space. No matter how efficiently you arrange the shelves, you can’t fit an infinite number of books in a single building. That’s when you need to start thinking about opening branch libraries. This is the approach of horizontal sharding. For Figma, horizontal sharding was a way to split large tables across multiple physical databases, allowing them to scale beyond the limits of a single machine. The below diagram shows this approach: However, horizontal sharding is a complex process that comes with its own set of challenges:

Exploring Alternative SolutionsThe engineering team at Figma evaluated alternative SQL options such as CockroachDB, TiDB, Spanner, and Vitess as well as NoSQL databases. Eventually, however, they decided to build a horizontally sharded solution on top of their existing vertically partitioned RDS Postgres infrastructure. There were multiple reasons for taking this decision:

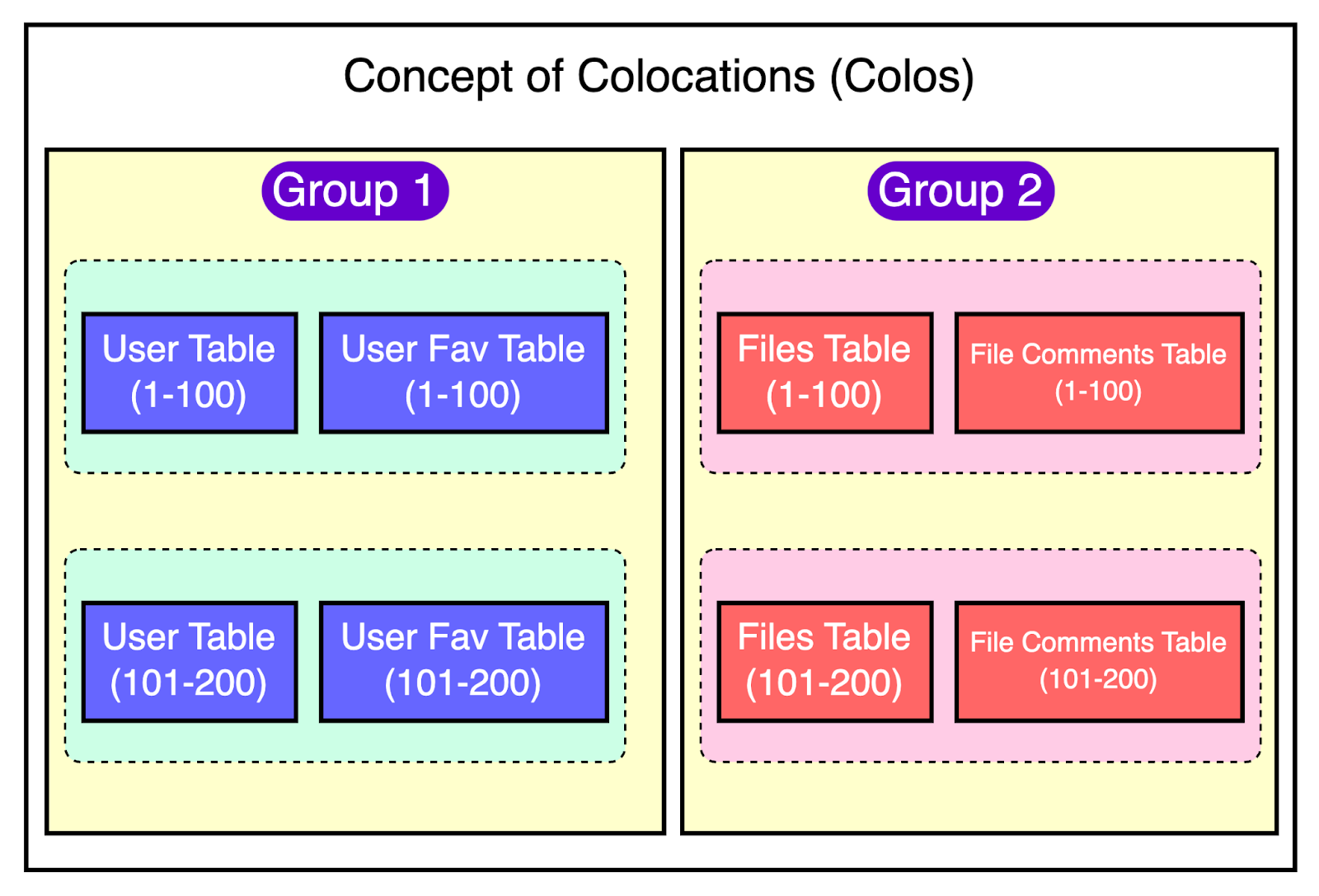

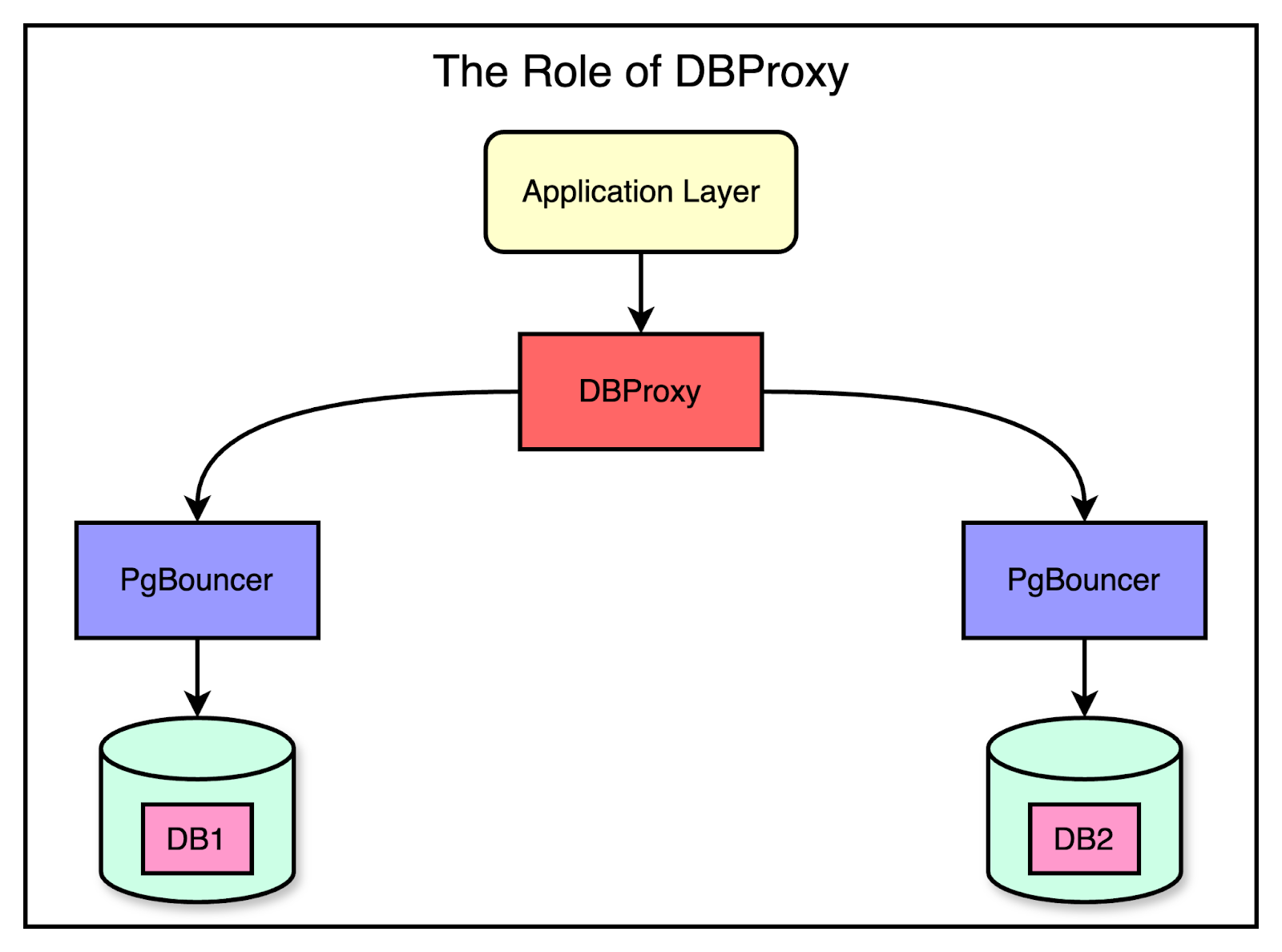

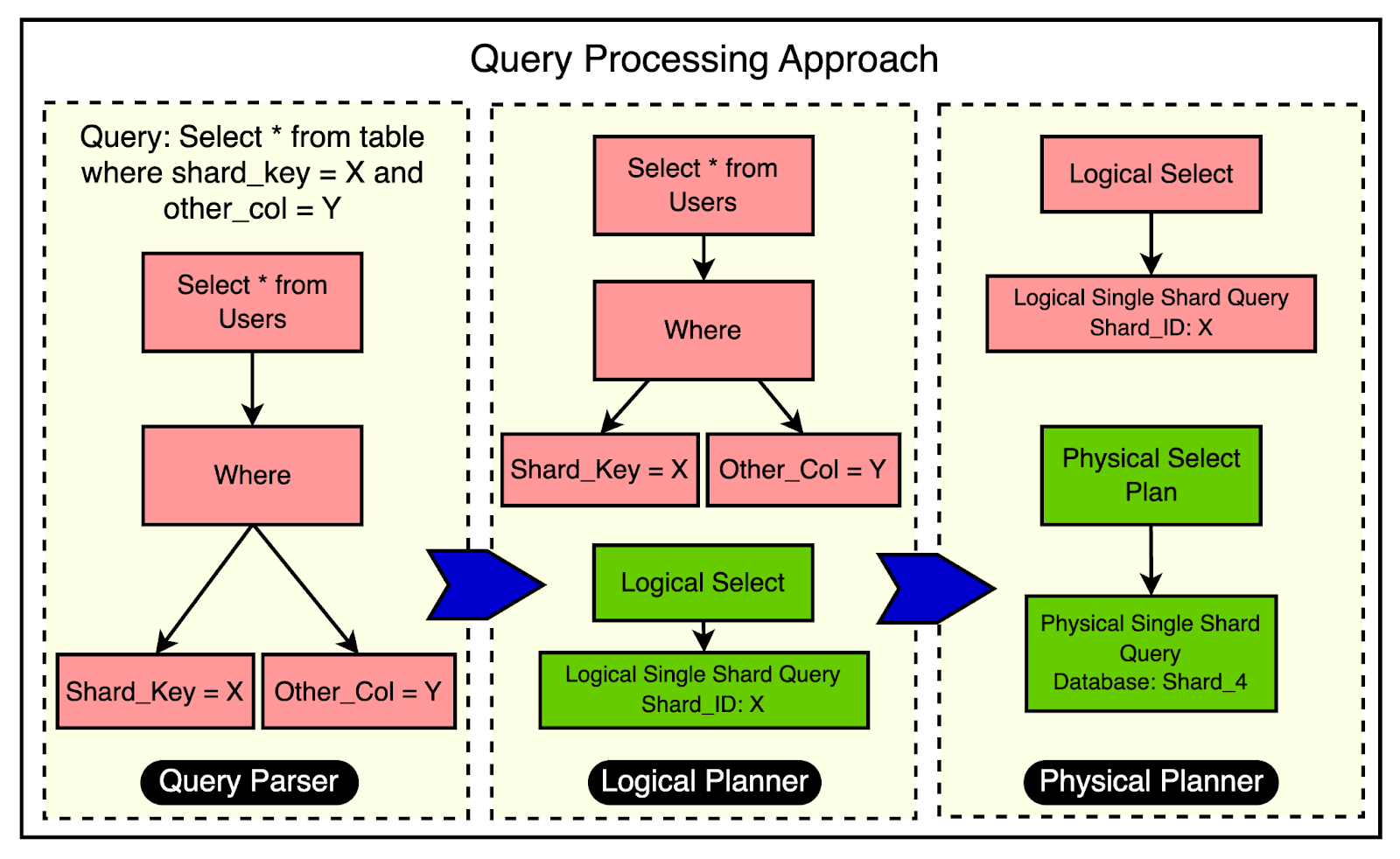

Figma’s Unique Sharding ImplementationFigma’s approach to horizontal sharding was tailored to their specific needs as well as the existing architecture. They made some unusual design choices that set their implementation apart from other common solutions. Let’s look at the key components of Figma’s sharding approach: Colos (Colocations) for Grouping Related TablesFigma introduced the concept of “colos” or colocations, which are a group of related tables that share the same sharding key and physical sharding layout. To create the colos, they selected a handful of sharding keys like UserId, FileId, or OrgID. Almost every table at Figma could be sharded using one of these keys. This provides a friendly abstraction for developers to interact with horizontally sharded tables. Tables within a colo support cross-table joins and full transactions when restricted to a single sharding key. Most application code already interacted with the database in a similar way, which minimized the work required by applications to make a table ready for horizontal sharding. The below diagram shows the concept of colos: Logical Sharding vs Physical ShardingFigma separated the concept of “logical sharding” at the application layer from “physical sharding” at the Postgres layer. Logical sharding involves creating multiple views per table, each corresponding to a subset of data in a given shard. All reads and writes to the table are sent through these views, making the table appear horizontally sharded even though the data is physically located on a single database host. This separation allowed Figma to decouple the two parts of their migration and implement them independently. They could perform a safer and lower-risk logical sharding rollout before executing the riskier distributed physical sharding. Rolling back logical sharding was a simple configuration change, whereas rolling back physical shard operations would require more complex coordination to ensure data consistency. DBProxy Query Engine for Routing and Query ExecutionTo support horizontal sharding, the Figma engineering team built a new service named DBProxy that sits between the application and connection pooling layers such as the PGBouncer. DBProxy includes a lightweight query engine capable of parsing and executing horizontally sharded queries. It consists of three main components:

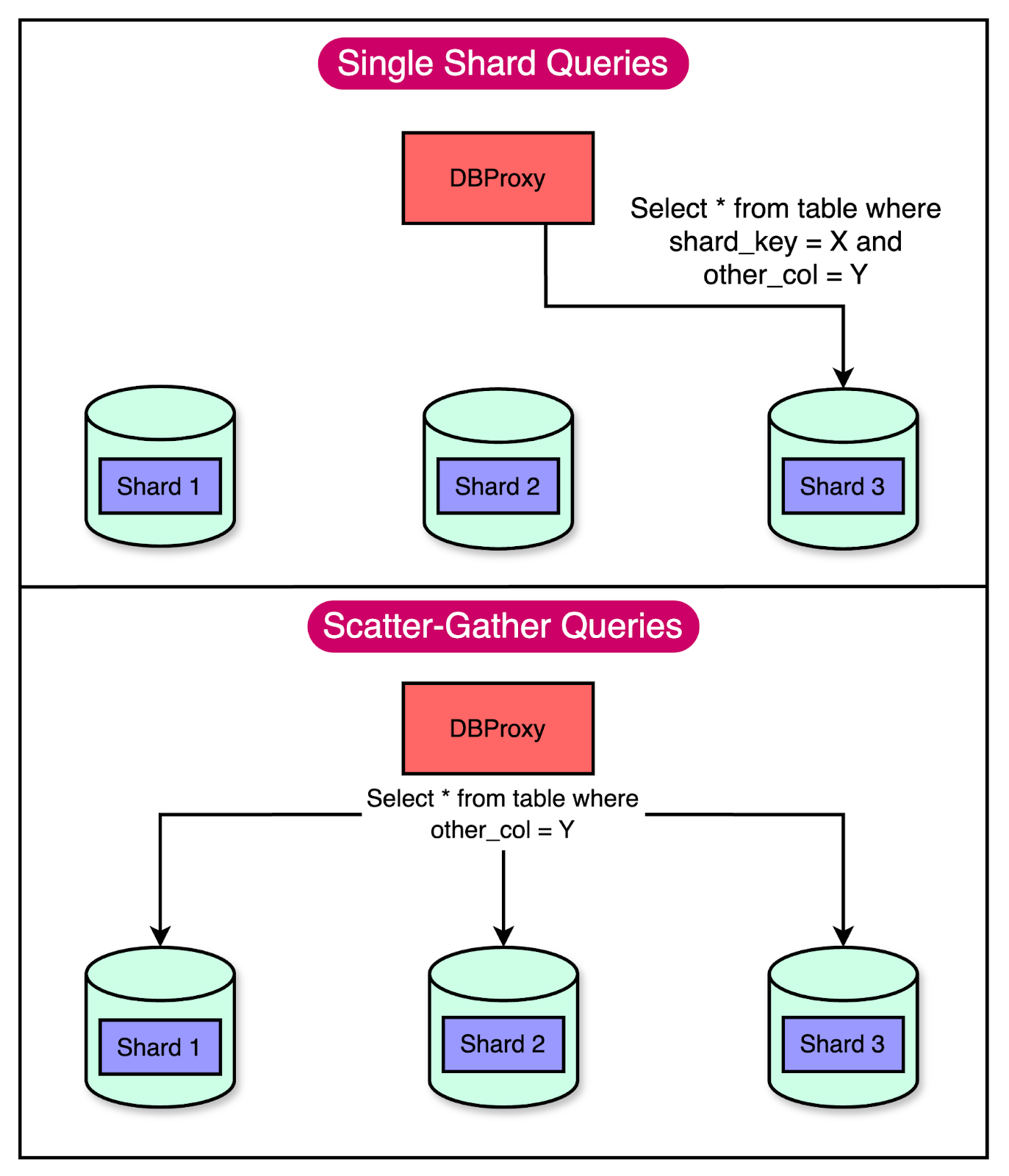

The below diagram shows the practical use of these three components within the query processing workflow. There are always trade-offs when it comes to queries in a horizontally sharded world. Queries for a single shard key are relatively easy to implement. The query engine just needs to extract the shard key and route the query to the appropriate physical database. However, if the query does not contain a sharding key, the query engine has to perform a more complex “scatter-gather” operation. This operation is similar to a hide-and-seek game where you send the query to every shard (scatter), and then piece together answers from each shard (gather). The below diagram shows how single-shard queries work when compared to scatter-gather queries. As you can see, this increases the load on the database, and having too many scatter-gather queries can hurt horizontal scalability. To manage things better, DBProxy handles load-shedding, transaction support, database topology management, and improved observability. Shadow Application Readiness FrameworkFigma added a “shadow application readiness” framework capable of predicting how live production traffic would behave under different potential sharding keys. This framework helped them keep the DBProxy simple while reducing the work required for the application developers in rewriting unsupported queries. All the queries and associated plans are logged to a Snowflake database, where they can run offline analysis. Based on the data collected, they were able to pick a query language that supported the most common 90% of queries while avoiding the worst-case complexity in the query engine. ConclusionFigma’s infrastructure team shipped their first horizontally sharded table in September 2023, marking a significant milestone in their database scaling journey. It was a successful implementation with minimal impact on availability. Also, the team observed no regressions in latency or availability after the sharding operation. Figma’s ultimate goal is to horizontally shard every table in their database and achieve near-infinite scalability. They have identified several challenges that need to be solved such as:

Lastly, after achieving a sufficient runway, they also plan to reassess their current approach of using in-house RDS horizontal sharding versus switching to an open-source or managed alternative in the future. References: SPONSOR USGet your product in front of more than 500,000 tech professionals. Our newsletter puts your products and services directly in front of an audience that matters - hundreds of thousands of engineering leaders and senior engineers - who have influence over significant tech decisions and big purchases. Space Fills Up Fast - Reserve Today Ad spots typically sell out about 4 weeks in advance. To ensure your ad reaches this influential audience, reserve your space now by emailing hi@bytebytego.com. © 2024 ByteByteGo |

by "ByteByteGo" <bytebytego@substack.com> - 11:36 - 7 May 2024