- Mailing Lists

- in

- Shipping to Production

Archives

- By thread 5285

-

By date

- June 2021 10

- July 2021 6

- August 2021 20

- September 2021 21

- October 2021 48

- November 2021 40

- December 2021 23

- January 2022 46

- February 2022 80

- March 2022 109

- April 2022 100

- May 2022 97

- June 2022 105

- July 2022 82

- August 2022 95

- September 2022 103

- October 2022 117

- November 2022 115

- December 2022 102

- January 2023 88

- February 2023 90

- March 2023 116

- April 2023 97

- May 2023 159

- June 2023 145

- July 2023 120

- August 2023 90

- September 2023 102

- October 2023 106

- November 2023 100

- December 2023 74

- January 2024 75

- February 2024 75

- March 2024 78

- April 2024 74

- May 2024 108

- June 2024 98

- July 2024 116

- August 2024 134

- September 2024 130

- October 2024 141

- November 2024 171

- December 2024 115

- January 2025 216

- February 2025 140

- March 2025 220

- April 2025 233

- May 2025 239

- June 2025 303

- July 2025 97

Your invitation: Join New Relic's user meetup in Amsterdam on 16 November

You’ve probably heard of Web3. But what is it, exactly?

Shipping to Production

Shipping to Production

This is a sneak peek of today’s paid newsletter for our premium subscribers. Get access to this issue and all future issues - by subscribing today. Latest articlesIf you’re not a subscriber, here’s what you missed this month.

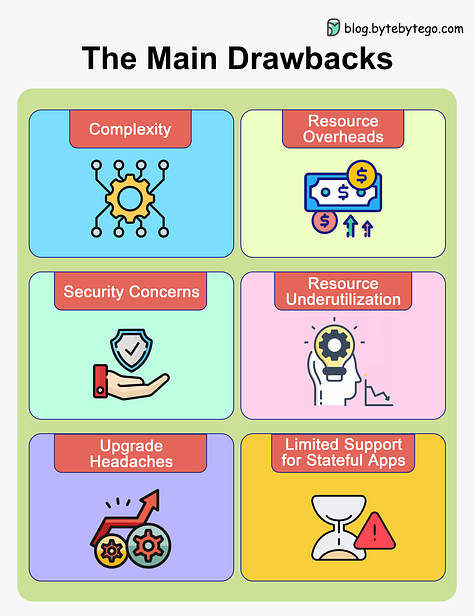

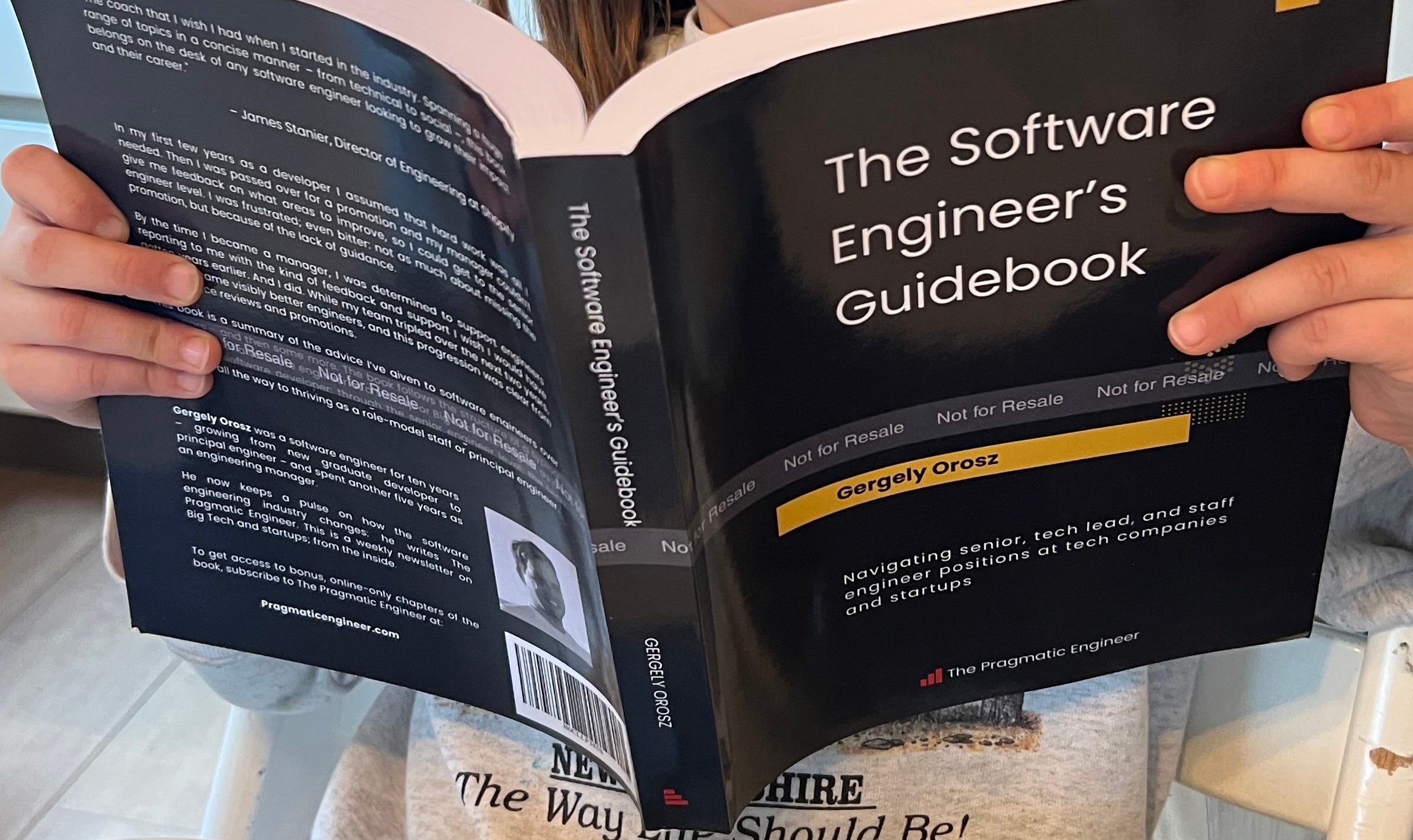

To receive all the full articles and support ByteByteGo, consider subscribing: A book that I have been waiting for a long time is finally out: The Software Engineer's Guidebook, written by Gergely Orosz, a software engineer and author of 'The Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter.' Since the book is out, I contacted Gergely to inquire whether he would be willing to share a chapter with the newsletter audience. To my delight, he kindly agreed. The chapter I've chosen is 'Shipping to Production.' I hope you enjoy it. You can check out the book here: The Software Engineer's Guidebook As a tech lead, you’re expected to get your team’s work into production quickly and reliably. But how does this happen, and which principles should you follow? This depends on several factors: the environment, the maturity of the product being worked on, how expensive outages are, and whether moving fast or having no reliability issues is more important. This chapter covers shipping to production reliably in different environments. It highlights common approaches across the industry, and helps you refine how your team thinks about this process. We cover:

1. EXTREMES IN SHIPPING TO PRODUCTIONLet’s start with two “extremes” in shipping to production: YOLO shippingThe You Only Live Once (YOLO) approach is used for many prototypes, side projects, and unstable products like alpha/beta versions. It’s also how some urgent changes make it into production. The idea is simple, make a change in production and check if it works in production. Examples of YOLO shipping include:

YOLO shipping is as fast as it gets when shipping a change to production. However, it also has the highest risk of introducing new issues into production because there is no safety net. For products with few to zero production users, the damage done by introducing bugs into production can be low, so this approach is justifiable. YOLO releases are common for:

As a software product grows and more customers rely on it, code changes need to go through extra validation before production. Let’s go to the other extreme: a team obsessed with doing everything possible to ship zero bugs into production. Thorough verification through multiple stagesThis is an approach used for mature products with many valuable customers, where a single bug can cause major problems. This rigorous approach is used if bugs could result in customers losing money, or make them switch to a competitor’s offering. Several verification layers are in place, with the goal of simulating the real world with greater accuracy, such as:

A heavyweight release process is used by:

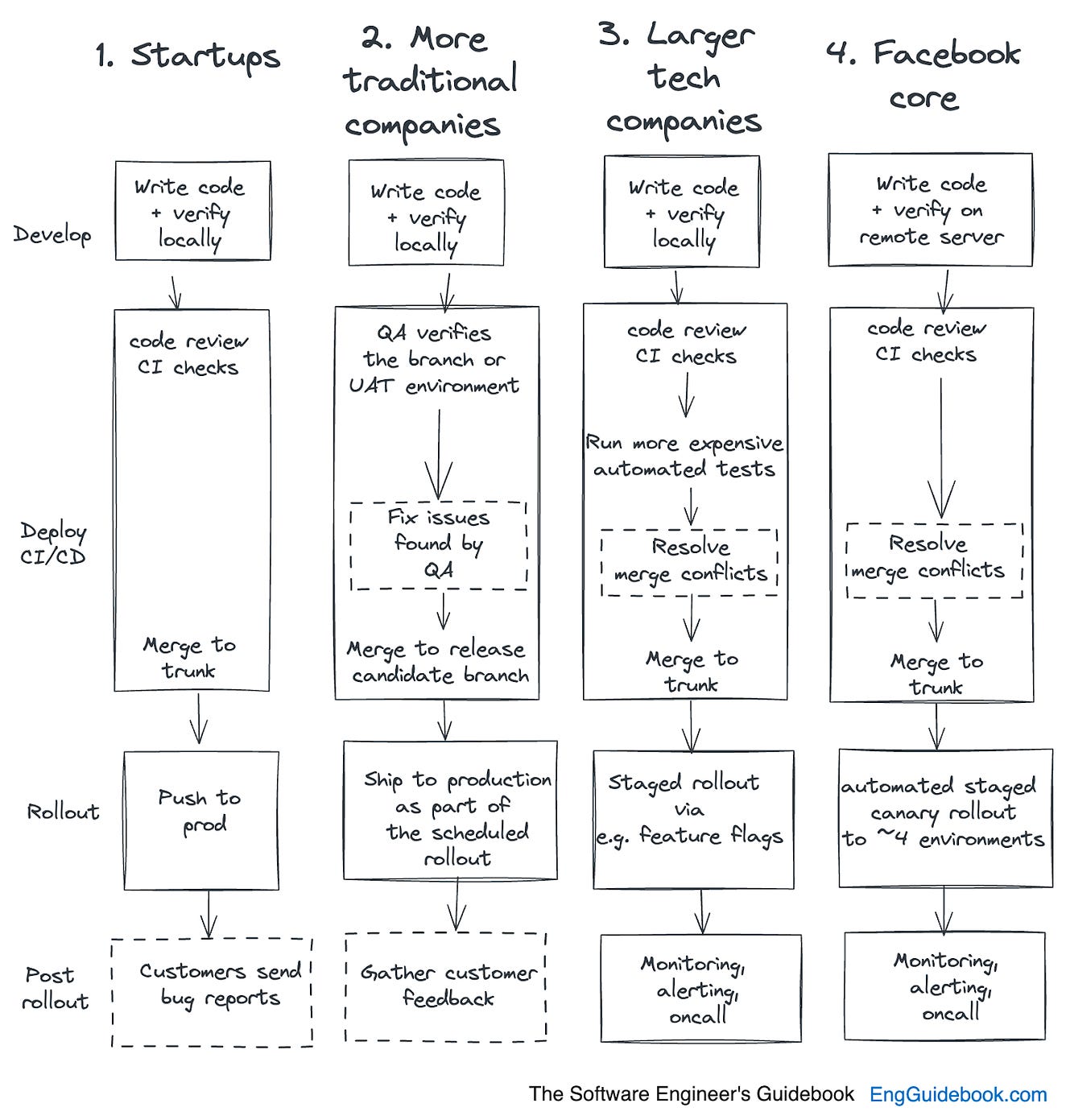

2. TYPICAL SHIPPING PROCESSESDifferent companies tend to take different steps in shipping to production. Below is a summary of typical approaches, highlighting the variety of processes: StartupsStartups typically do fewer quality checks. These companies tend to prioritize moving fast and iterating quickly, and often do so without much of a safety net. This makes perfect sense if they don't have customers yet. As customers arrive, teams need to find ways to avoid regressions and the shipping of bugs. Startups are usually too small to invest in automation, and so most do manual QA – including the founders being the ‘ultimate’ testers, while some places hire dedicated QA folks. As a company finds its product-market fit, it’s more common to invest in automation. And at tech startups that hire strong engineering talent, these teams can put automated tests in place from day one. Traditional companiesThese places tend to rely more heavily on QAs teams. Automation is sometimes present at more traditional companies, but typically they rely on large QA teams to verify what is built. Working on branches is also common; it's rare to have trunk-based development. Code mostly gets pushed to production on a weekly schedule or even less frequently, after the QA team verifies functionality. Staging and UAT (User Acceptance Testing) environments are more common, as are larger, batched changes shipped between environments. Sign-off is required from the QA team, the product manager, or the project manager, in order to progress the release to the next stage. Large tech companiesThese places typically invest heavily in infrastructure and automation related to shipping with confidence. Such investments often include automated tests which run quickly and deliver rapid feedback, canarying, feature flags and staged rollouts. These companies aim for a high quality bar, but also to ship immediately when quality checks are complete, working on trunk. Tooling to deal with merge conflicts becomes important, given that some places can make over 100 changes on trunk per day. For details on QA at Big Tech, see the article How Big Tech does QA. Meta’s core productFacebook, as a product and engineering team, merits a separate mention, because this organization has a sophisticated and effective approach few other companies use. This Meta product has fewer automated tests than many would assume, but on the other hand, Facebook has an exceptional automated canarying functionality, where the code is rolled out through 4 environments, from a testing environment with automation, through one that all employees use, then through a test market that is a smaller geographical region, and finally to all users. At each stage, the rollout automatically halts if the metrics are off. 3. PRINCIPLES AND TOOLSWhat are principles and approaches worth following for shipping changes to production responsibly? Consider these: Development environmentsUse a local or isolated development environment. Engineers should be able to make changes on their local machine, or in an isolated environment unique to them. It’s more common for developers to work in local environments. However, places like Meta are shifting to remote servers for each engineer. From the article, Inside Facebook’s Engineering culture:

Verify locally. After writing the code, do a local test to ensure it works as expected. Testing and verificationConsider edge cases and test for them. Which obscure cases does your code change need to account for? Which real-world use cases haven’t you accounted for yet? Before finalizing work on the change, compile a list of edge cases. Consider writing automated tests for them, if possible. At least do manual testing. Coming up with a list of unconventional edge cases is a task for which QA engineers or testers can be very helpful. Write automated tests to validate your changes. After manually verifying your changes, exercise them with automated tests. If following a methodology like test driven development (TDD,) you might do this the other way around by writing automated tests first, then checking that your code change passes them. Another pair of eyes: a code review. With your code changes complete, put up a pull requests and get somebody with context to look at your code changes. Write a clear, concise description of the changes, which edge cases are tested for, and get a code review. All automated tests pass, minimizing the risk of regressions. Before pushing the code, run all the existing tests for the codebase. This is typically done automatically, via the CI/CD system (continuous integration/continuous deployment.)... Keep reading with a 7-day free trialSubscribe to ByteByteGo Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.A subscription gets you:

© 2023 ByteByteGo |

by "ByteByteGo" <bytebytego@substack.com> - 11:38 - 7 Nov 2023