- Mailing Lists

- in

- Why is Kafka so fast? How does it work?

Archives

- By thread 5343

-

By date

- June 2021 10

- July 2021 6

- August 2021 20

- September 2021 21

- October 2021 48

- November 2021 40

- December 2021 23

- January 2022 46

- February 2022 80

- March 2022 109

- April 2022 100

- May 2022 97

- June 2022 105

- July 2022 82

- August 2022 95

- September 2022 103

- October 2022 117

- November 2022 115

- December 2022 102

- January 2023 88

- February 2023 90

- March 2023 116

- April 2023 97

- May 2023 159

- June 2023 145

- July 2023 120

- August 2023 90

- September 2023 102

- October 2023 106

- November 2023 100

- December 2023 74

- January 2024 75

- February 2024 75

- March 2024 78

- April 2024 74

- May 2024 108

- June 2024 98

- July 2024 116

- August 2024 134

- September 2024 130

- October 2024 141

- November 2024 171

- December 2024 115

- January 2025 216

- February 2025 140

- March 2025 220

- April 2025 233

- May 2025 239

- June 2025 303

- July 2025 156

Some US drones may now fly across states. What are the benefits of drone deliveries?

Keep Your Transport Vehicles Safe and Efficient with Tire Pressure Monitoring Systems

Why is Kafka so fast? How does it work?

Why is Kafka so fast? How does it work?

This is a sneak peek of today’s paid newsletter for our premium subscribers. Get access to this issue and all future issues - by subscribing today. Latest articlesIf you’re not a subscriber, here’s what you missed this month. To receive all the full articles and support ByteByteGo, consider subscribing: With data streaming into enterprises at an exponential rate, a robust and high-performing messaging system is crucial. Apache Kafka has emerged as a popular choice for its speed and scalability - but what exactly makes it so fast? In this issue, we'll explore:

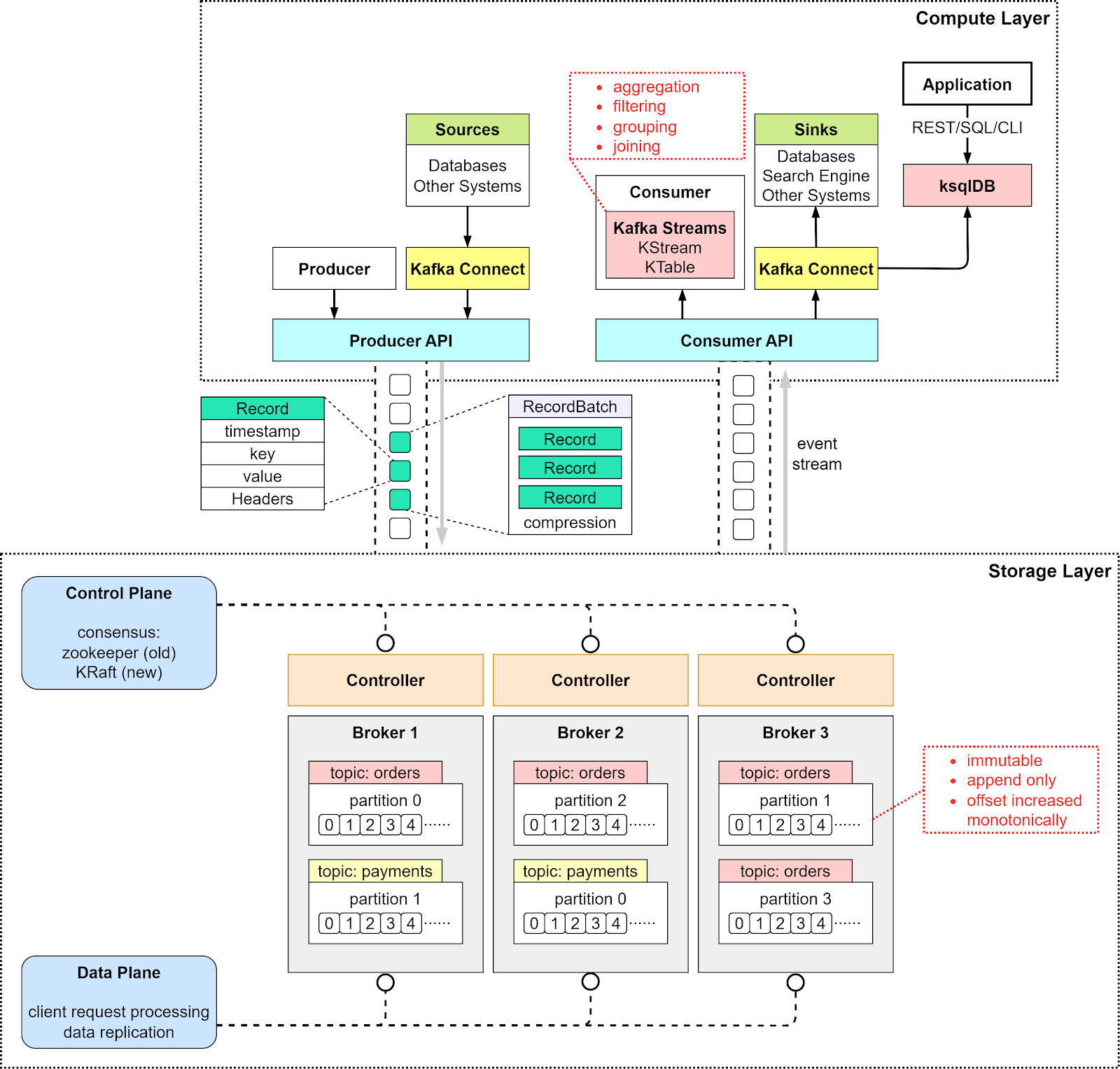

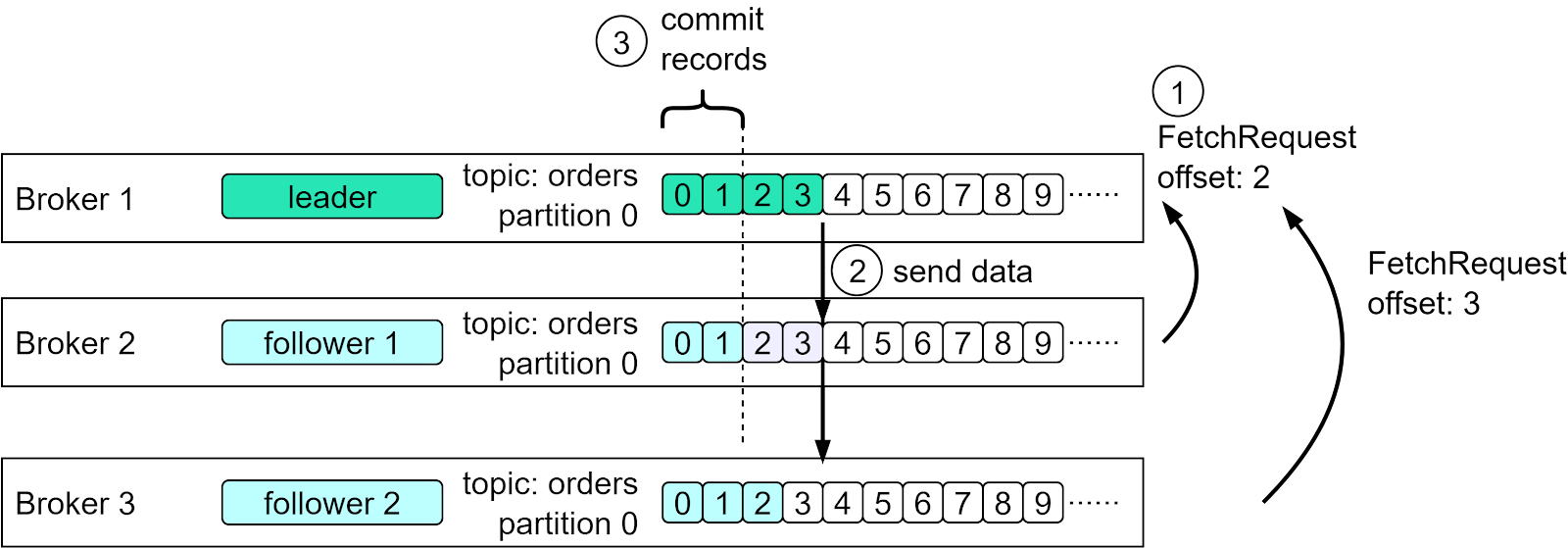

Let’s dive into Kafka’s core components first. Kafka Architecture DistilledIn a typical scenario where Kafka is used as a pub-sub messaging middleware, there are 3 important components: producer, broker, and consumer. The producer is the message sender, and the consumer is the message receiver. The broker is usually deployed in a cluster mode, which handles incoming messages and writes them to the broker partitions, allowing consumers to read from them. Note that Kafka is positioned as an event streaming platform, so the term “message”, which is often used in message queues, is not used in Kafka. We call it an “event”. The diagram below puts together a detailed view of Kafka’s architecture and client API structure. We can see that although the producer, consumer, and broker are still key to the architecture, it takes more to build a high-throughput, low-latency Kafka. Let’s go through the components one by one. From a high-level point of view, there are two layers in the architecture: the compute layer and the storage layer. The Compute LayerThe compute layer, or the processing layer, allows various applications to communicate with Kafka brokers via APIs. The producers use the producer API. If external systems like databases want to talk to Kafka, it also provides Kafka Connect as integration APIs. The consumers talk to the broker via consumer API. In order to route events to other data sinks, like a search engine or database, we can use Kafka Connect API. Additionally, consumers can perform streaming processing with Kafka Streams API. If we deal with an unbounded stream of records, we can create a KStream. The code snippet below creates a KStream for the topic “orders” with Serdes (Serializers and Deserializers) for key and value. If we just need the latest status from a changelog, we can create a KTable to maintain the status. Kafka Streams allows us to perform aggregation, filtering, grouping, and joining on event streams. While Kafka Streams API works fine for Java applications, sometimes we might want to deploy a pure streaming processing job without embedding it into an application. Then we can use ksqlDB, a database cluster optimized for stream processing. It also provides a REST API for us to query the results. We can see that with various API support in the compute layer, it is quite flexible to chain the operations we want to perform on event streams. For example, we can subscribe to topic “orders”, aggregate the orders based on products, and send the order counts back to Kafka in the topic “ordersByProduct”, which another analytics application can subscribe to and display. The Storage LayerThis layer is composed of Kafka brokers. Kafka brokers run on a cluster of servers. The data is stored in partitions within different topics. A topic is like a database table, and the partitions in a topic can be distributed across the cluster nodes. Within a partition, events are strictly ordered by their offsets. An offset represents the position of an event within a partition and increases monotonically. The events persisted on brokers are immutable and append-only, even deletion is modeled as a deletion event. So, producers only handle sequential writes, and consumers only read sequentially. A Kafka broker’s responsibilities include managing partitions, handling reads and writes, and managing replications of partitions. It is designed to be simple and hence easy to scale. We will review the broker architecture in more detail. Since Kafka brokers are deployed in a cluster mode, there are two necessary components to manage the nodes: the control plan and the data plane. Control PlaneThe control plane manages the metadata of the Kafka cluster. It used to be Zookeeper that managed the controllers: one broker was picked as the controller. Now Kafka uses a new module called KRaft to implement the control plane. A few brokers are selected to be the controllers. Why was Zookeeper eliminated from the cluster dependency? With Zookeeper, we need to maintain two separate types of systems: one is Zookeeper, and the other is Kafka. With KRaft, we just need to maintain one type of system, which makes the configuration and deployment much easier than before. Additionally, KRaft is more efficient in propagating metadata to brokers. We won’t discuss the details of the KRaft consensus here. One thing to remember is the metadata caches in the controllers and brokers are synchronized via a special topic in Kafka. Data PlaneThe data plane handles the data replication. The diagram below shows an example. Partition 0 in the topic “orders” has 3 replicas on the 3 brokers. The partition on Broker 1 is the leader, where the current data offset is at 4; the partitions on Broker 2 and 3 are the followers where the offsets are at 2 and 3. Step 1 - In order to catch up with the leader, Follower 1 issues a FetchRequest with offset 2, and Follower 2 issues a FetchRequest with offset 3. Step 2 - The leader then sends the data to the two followers accordingly. Step 3 - Since followers’ requests implicitly confirm the receipts of previously fetched records, the leader then commits the records before offset 2. RecordKafka uses the Record class as an abstraction of an event. The unbounded event stream is composed of many Records. There are 4 parts in a Record:

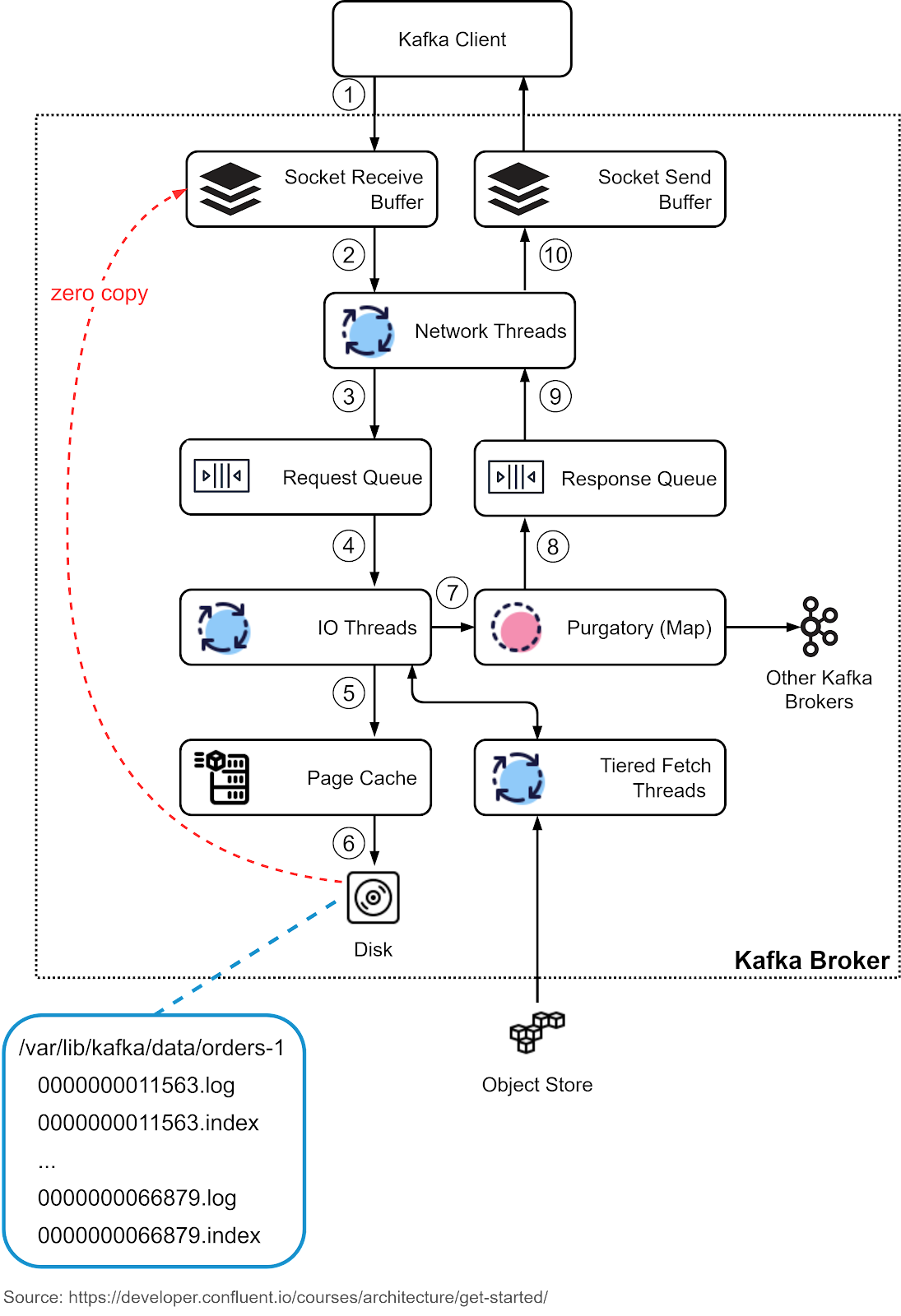

The key is used for enforcing ordering, colocating the data that has the same key, and data retention. The key and value are byte arrays that can be encoded and decoded using serializers and deserializers (serdes). BrokerWe discussed brokers as the storage layer. The data is organized in topics and stored as partitions on the brokers. Now let’s look at how a broker works in detail. Step 1: The producer sends a request to the broker, which lands in the broker’s socket receive buffer first. Steps 2 and 3: One of the network threads picks up the request from the socket receive buffer and puts it into the shared request queue. The thread is bound to the particular producer client. Step 4: Kafka’s I/O thread pool picks up the request from the request queue. Steps 5 and 6: The I/O thread validates the CRC of the data and appends it to a commit log. The commit log is organized on disk in segments. There are two parts in each segment: the actual data and the index. Step 7: The producer requests are stashed into a purgatory structure for replication, so the I/O thread can be freed up to pick up the next request. Step 8: Once a request is replicated, it is removed from the purgatory. A response is generated and put into the response queue. Steps 9 and 10: The network thread picks up the response from the response queue and sends it to the corresponding socket send buffer. Note that the network thread is bound to a certain client. Only after the response for a request is sent out, will the network thread take another request from the particular client. Keep reading with a 7-day free trialSubscribe to ByteByteGo Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.A subscription gets you:

© 2023 ByteByteGo |

by "ByteByteGo" <bytebytego@substack.com> - 11:39 - 14 Sep 2023